I should start this post by stating something very clearly – I am not a blue sky thinker. I not a person to ‘think outside the box’ or ‘delayer problems’ or whatever other management bollocks you like to come up with for it. But I am a supporter of it – thinking creatively on how to tackle known issues that are not limited by current thinking. It is healthy to challenge established thinking and procedures, and I fully support creative solutions.

Blue sky thinking and transport, in my experience, has a sticky history. Transport is a very practical business. It is driven by rules and procedure, with practical problems requiring practical solutions.

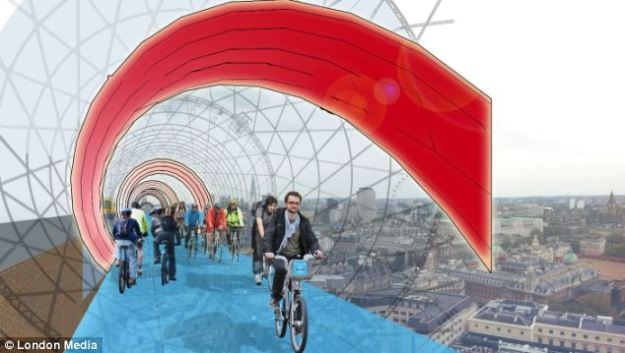

A recent announcement, or should I say re-announcement, got me thinking about the applicability of blue sky thinking in transport. Lord Foster’s latest (re)announcement of plans for SkyCycle, a network of raised cycle tracks above railway lines in London accessible by ramps to street level, certainly strikes me as a blue sky thinking project. Lord Foster does his best at a sales pitch for the project:

“I believe that cities where you can walk or cycle rather than drive are more congenial places in which to live, To improve the quality of life for all in London and to encourage a new generation of cyclists, we have to make it safe. However, the greatest barrier to segregating cars and cyclists is the physical constraint of London’s streets, where space is already at a premium. SkyCycle is a lateral approach to finding space in a congested city. By using the corridors above the suburban railways, we could create a world-class network of safe, car free cycle routes that are ideally located for commuters.”

SkyCycle. Image from Foster and Partners

That distinguished architectural minds such as that of Lord Foster are paying attention to how we can make cycling safer in our cities should be welcomed. I have no doubt that he is a clever guy, but sadly this proposed solution shows the danger of blue sky thinking – by coming up with a radical solution to a problem, you don’t actually solve the problem.

Lord Foster actually puts the finger directly on the problem – making cycling safe. But this solution only tackles part of it. The fundamental problem that is not tackled is making our streets safe for cycling. I don’t imagine that Lord Foster pretends that this plan is the magic solution that makes everybody want to cycle, nor should it distract from making our streets safe. But making our streets safe for cycling simply has to take priority.

Reading the public information on the scheme, it is clear to me that rather than the focus of SkyCycle being on safety, the focus is on capacity and speed. Reducing commuter journey times and providing capacity for up to 12000 cyclists per hour are laudable aims, but I thought that we as transport professionals were moving away from simple speed and capacity to measure scheme success? Subjective safety and route attractiveness (and I don’t just mean that as in the colours on the route look pretty as indicated in artist impressions of SkyCycle) are just two further criteria that I can think of.

This is where the second issue of blue sky thinking comes into play – distracting from other, more comprehensive and meaningful solutions. Streets are where life in our towns and cities takes place, where vulnerable road users face the greatest dangers and are in greatest need of our expertise on making them safe. Junctions, lack of segregated links on major roads, and poor permeability are just a few of the myriad of issues facing cyclists everyday at street level. Shoving them up in the sky does not tackle any of those issues, and at worst will distract decision makers and funding providers from tackling these issues.

It is reassuring to see that, publicly at least, Transport for London’s response to the SkyCycle idea has been nothing beyond considering the idea, as highlighted by As Easy As Riding a Bike. Network Rail seem very supportive of the idea, and why not? What they will get is a way of reducing overcrowding on peak hour inner-suburban trains through building an asset that I am very sure they won’t be responsible for maintaining.

The final issue with blue sky thinking is that bad ideas – ok, perhaps not bad, but say less desirable – become implanted in the imagination, and once done so is very hard to shift. We have already mentioned this regarding zombie road schemes, where poor schemes developed with the best intentions never get fully killed off purely because decision makers think that it is a good idea, but is ‘not a priority right now’ or ‘there are not enough funds available’, without being given the thorough critical review required of every transport scheme.

It is often said that in transport circles there is a preference for projects that make a statement as opposed to projects that just get on with it quietly by simply working. Ask a politician to open either a new link road or a new cycle path, and most will prefer the former because of the statement that it sends out. Schemes that are ‘modern’ or ‘futuristic’ also score well on this, though how vertically-separated routes are futuristic is beyond me. Buchanan anyone?

That is my fundamental worry with SkyCycle. By focusing on a piece of infrastructure that is expensive and of little practical benefit, both attention and funding will be drawn from proven, tried-and-tested, and deliverable schemes that will deliver real benefits to cyclists.

Blue sky thinking in transport is great, as it allows us to innovate and think of solutions to problems that can be delivered practically. But that is so long as such thinking is grounded in practicality. SkyCycle is a nice idea, but until we make our streets safer for cyclists, its going on my nice to have list.

Now, Lord Foster, can you come up with some imaginative ways to improve our streets for cyclists? That is something that I would be very interested in hearing.

GroundCycle: Because pies in the sky (cycle) require a coffee-perky foundation.